For Teachers

Kindergarten to 12th grade

Tips for Teachers

Teacher Training

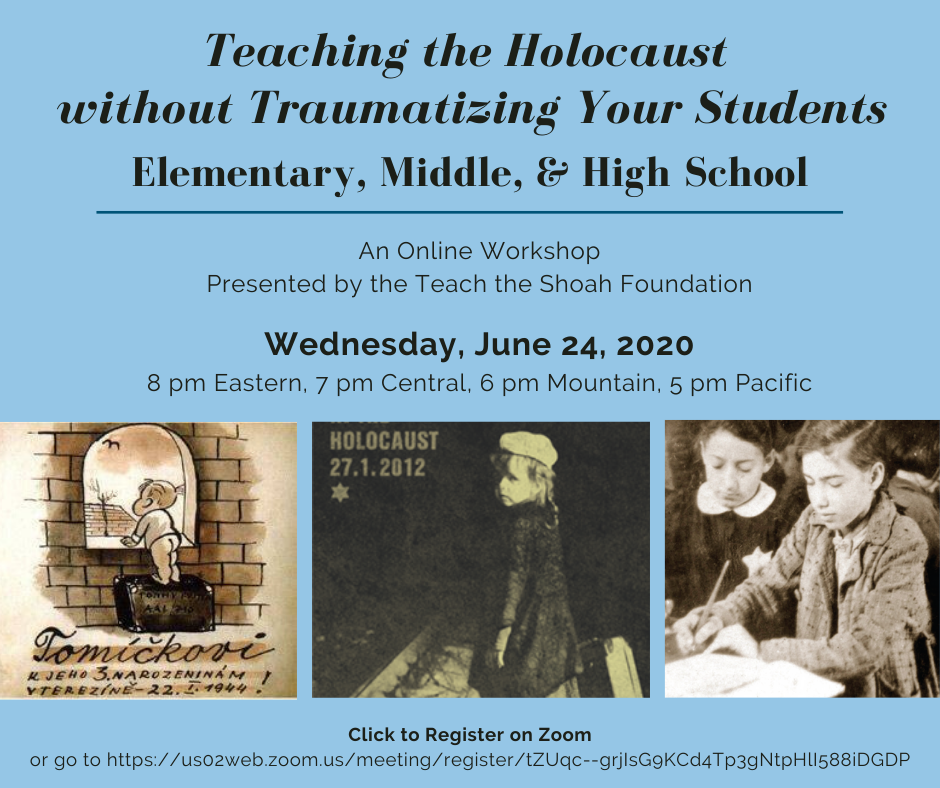

Upcoming Workshops

Online and In-Person

Sign up for teacher training workshops to help you teach the Holocaust in all settings and at all grade levels. See a list of upcoming workshops here.

The Holocaust is something that happened to our people. It does not define us as Jews. But understanding how they fought for their Judaism can enrich our own.

Teaching through Story

Real people, real stories

Much of Holocaust education has been focused on trying to understand the scale of the disaster, the huge number of people lost. Numbers like this have little meaning. Numbers do not tell us about the actual depth of the disaster. And numbers perpetuate the dehumanization of our ancestors.

Telling the stories of individuals can give us a much more complex and compelling story than trying to fathom the meaning of more than six million murders. The victims of this atrocity were real people with real stories, and we can teach all the pieces of the story of the Holocaust by telling individuals’ stories.

Here are some hints about how to use the stories and curriculum you find here to teach about the Holocaust.

Note: Throughout this website, we focus on the experience of the Jews and the treatment we received simply for being who we were. However, we must never forget the mixed multitude that died with us simply for being who they were: Roma people, gay people, those with disabilities, the voices of resistance, and many others.

Whose Story are We Telling?

“Pulled from the bunkers by force” in the Warsaw Ghetto. A picture of a people crushed beneath the unstoppable force of the Nazi machine.

When we think about the pictures from the Holocaust, we think of pictures of the dead and dying, of gaunt bodies and empty eyes, of trouble and fear. These images, along with all the Nazi propaganda, continue the Nazis’ work by showing Jews as something less than human.

For two generations, we have used the Nazis’ pictures to tell the story of what they did to us.

It is time to reclaim the humanity of our ancestors.

In the depths of chaos, the Jews recognized that unless they documented what was happening, their story would only be told by the perpetrators. They left diaries and writings, stories, art, and music – and they hid these in places where we could later find them. We can use this legacy to give the victims back their names, their faces, their voices, and their humanity.

Choose the victims’ story, not the perpetrators’

The Kovno Ghetto orchestra. The orchestras continued to play music by non-Jewish composers, in spite of laws forbidding it.

When we listen to the voices of our ancestors, we hear a story that acknowledges that many people died, but also that many people lived. This new story asks, How did they live? How did they survive? What did they hold onto?

When we follow this path, we find our ancestors holding onto those things that they felt most important – their love, their families, and their traditions, but also their community, their art, and their music. We see pictures of life and living, of families and communities, of joy as well as sorrow.

We acknowledge the inner strength of so many, even in the face of chaos, terror, and destruction.

Stories of Strength

There are recurring themes that can be seen in the stories we recommend. These themes include continuing to educate their children, to make music and art, and to celebrate their Judaism, and to continue to do so in the face of chaos, terror, and laws that forbid all of these actions. There are, of course, stories of physical resistance, but physical resistance starts as spiritual resistance. Even the stories of physical resistance start with stories of not allowing themselves to be turned into something less than human, of not allowing the Nazis to take away their Judaism.

When we teach from the perpetrators’ perspective, our students learn about all the things we were forbidden to do. When we teach from our ancestors’ perspective, our students learn, as it says in the diary of Chaim Kaplan, teacher and educator in the Warsaw ghetto, “In these days of our misfortune, we live the life of Marranos. Everything is forbidden to us, and yet we do everything.”

In a world of chaos, our ancestors tried to maintain normal life as much as possible. When their children were forbidden to attend school, they found ways to keep teaching them. They home-schooled them or formed hidden schools in the ghettos. In spite of laws making the practice of Judaism punishable by death, every ghetto had services in hiding. Many ghettos had theaters and orchestras, where, in spite of laws to the contrary, musicians continued to play the music of non-Jews such as Mozart, Beethoven, and Bach.

In the face of grave deprivation, our ancestors asked their rabbis what to do and found ways to continue to practice. The questions and responses from the rabbis in the ghettos are fascinating. When you can’t get candles, you can turn on an electric light and say the Shabbat candle-lighting blessing over it. If you can’t get wine, you can use sweet tea to celebrate Passover.

The Skarzysko-Kamienna Shofar, made in a labor camp in anticipation of Rosh Hashanah 5704 (1943).

Even in the camps, services continued in hiding, quietly. Stories are told of poetry discussions in the bunkers at Auschwitz. Survivor Moshe Winterter tells a terrifying and uplifting story about making a shofar in the labor camp of Skarzysko-Kamienna in Poland, at the request of his Rabbi.

There is no question that some people lost all hope under the pressure of the chaos and terror. Everyone who survived came out scarred both physically and emotionally. But many people found ways to live, and even to hope, in spite of the chaos and fear. Focusing on the strength of our ancestors, rather than the power of the victimization, gives our students a compelling story from which they can learn.

Putting the Trauma in Context

The Holocaust was just one part of these people’s lives. Here are some hints for keeping that in perspective.

Genia Bletcher, a gifted pianist, was active in the Vilna Ghetto theater.

As much as possible, always use people’s names. Using people’s names is one of the ways we give them back their humanity and rescue them from being just one in a pile of bodies. Real names also make the stories more powerful and salient to our students.

Remember that they were regular people. The Jews in the Holocaust were as varied as Jews are today. In spite of the image that many of us have, they were not, for the most part, shtetl Jews living Fiddler on the Roof lives. Some were religious, some were not. Some lived in the city, some in the country. They spoke many different languages: Yiddish, German, Polish, Dutch, Russian, French, Greek, even Arabic. They were doctors and dressmakers, scientists and shopkeepers, athletes and artists, weavers and welders. They did all the same sorts of things we do – went to school, went to work, played sports, went on vacation.

Do not get ahead of yourself in the story. The people whose stories we are telling did not know where the story was going. In 1939, they did not know that in 1942 they would be sent to camps and gas chambers. Even the Nazis did not know. There was no master plan from the beginning; the Nazis were making it up as they went along.

It is essential that we do not layer our knowledge of what was to come onto their actions. They were acting with the knowledge they had, not with the knowledge we have.

There is one exception to this, however: when talking to children, especially young children, always start the story at the end, with the survivor all grown up and happy. This allows the children to listen to stories of scary things happening without worrying about what will ultimately happen to the child in the story. What age is old enough to switch, to allow the ending to be a surprise? That will depend on your students, but may not be until high school.

Who were they before the terrible things happened to them?

When the Jews were forced into ghettos and camps, they tried to recreate those things they felt were most important to them. For some, that meant schools and synagogues; for others, theater and orchestras. Unless we understand who they were before 1933, before their lives became confined by racist laws and pogroms, we cannot understand why they reacted as they did. We cannot see their humanity.

Who were they after? Similarly, to end in 1945 leaves the survivors as nameless near-corpses in the camps and as terrified children cowering in hiding places or lying about their identities. In 1945, even at liberation, they were still victims. We must show our students the path our ancestors took from victim to survivor, how they stepped out of the ashes and the bunkers, found a way past the anger and the sorrow, and rebuilt their lives.

Enriching our Judaism

One of the most difficult aspects of teaching the Holocaust is helping our students to understand how to integrate it into their own lives. Can you maintain your faith in the world, in G-d, in Judaism, in the face of the Holocaust? To say, as we have for so long, “You must be Jewish for the millions who died,” fails to recognize that each individual must be Jewish for themselves and in their own way.

They fought for their Judaism: Chanukah in the Westerbork transit camp, Holland, 1943.

They fought for their Judaism: Chanukah in the Westerbork transit camp, Holland, 1943.

Emphasizing strength, rather than victimization, can help us, and our students, find ways to integrate this story into our own faith and lives. For two generations, we have let this story define us as victims. Defining themselves as victims is a difficult idea for young Jews, especially American Jews, to integrate into their own lives. They do not feel like victims, and they do not want to be victims. Therefore, do not say, “Jews are victims.” Say, rather, “During the Holocaust, the Jews were the victims.” This is a very different statement, and one that we and our students can easily integrate into our understanding of ourselves.

But even during the Holocaust, our ancestors did not simply roll over and let the Nazis tell them what to do. Many Jews responded with an inner strength that held fast, even in the face of terror. Survivor Rivka Wagner has a wonderful answer for when people insist she should have lost her faith in G-d because of what happened to her: “Our faith was the one thing they could not take from us.” We can enrich our own Judaism by understanding how our ancestors fought for and held onto their Judaism, and how their Judaism served to help them hold onto their sanity and even to some hope.

Age-Appropriate Holocaust Education

Building a Foundation

If we want our older students to engage with the complexity of the Holocaust, we cannot wait until they are in middle school to start teaching them about the Holocaust. We must build a foundation of understanding for them, starting at a young age.

At each age, we must carefully design our lessons to what we feel the students can handle. We need to tell TRUE or realistic stories but we DO NOT need to tell the WHOLE story at every age. By keeping our lessons age-appropriate, our students can grow into a deeper understanding of the Holocaust and its stories.

Why You Should Start Young

We know that it is not appropriate to tell second graders about that time when their great-grandparents were rounded up and shot for being Jews. On the other hand, if we wait until middle or high school to even mention the Holocaust, then our students will be unable to deal with the complexities of the story. The Holocaust makes one question every aspect of life – culture, history, democracy, even G-d. It is imperative that we allow our students to work through these questions in a space where we can help them, rather than forcing them to work through these questions alone.

We must, therefore, build a foundation upon which our students can lay the more difficult parts of the story. If we build them a foundation, then when they get to high school, we will be able to talk about the difficult questions that the Holocaust raises.

Discussing the Holocaust with young children takes careful planning. At the youngest ages, we can teach about ghettos and the loss of home or freedom. At this age, we avoid teaching about the loss of family, which is much more difficult for young children. The key point here is that although we must tell true stories, we do not need to tell the whole story at every age. We must carefully design our lesson plans to what we feel the students at each age can handle.

Our Recommendations for What's Age-Appropriate

Every class is different and you should determine what is age-appropriate based on your knowledge of the maturity of your class. Nonetheless, here is an idea of what you can expect to be appropriate at each level. Try to avoid mentioning ideas that are only age-appropriate at older ages.

All Ages: Life before the war; Life after the war

Grades K-2: Moving to the ghettos; Hiding; Intact families (although one parent may be lost)

Grades 3-5: Living in the ghetto; Living in hiding; Kindertransport; Broken families

Grades 6-8: The difficulty of life in the ghetto; Deportation; Labor Camps

Grades 9-12: Mass murder, including gas chambers and killing pits

College/Adult: Medical experiments (e.g. Mengele)

Safety Nets for Elementary Students

How we present the stories to the children can make a big difference in how much difficulty they have with the lessons of the Holocaust. Here are some safety nets that we recommend to prevent trauma among younger students.

1. Tell stories of survivors, starting with the protagonist as a grown up wanting to tell us about something that happened when they were young. This way our students never worry about whether the protagonist in the story will get through the difficulties.

2. Emphasize that this happened a long time ago in a faraway place. By adding distance, we reduce the likelihood that the students will become fearful something similar could happen to them. (Note that we may want middle and high schoolers to consider this issue but it is too traumatic for elementary schoolers, especially the younger ones.)

3. Emphasize that the children had loving families. For the youngest students (K-3), those families should remain intact throughout the story. This safety net recognizes that for children, safety is not in a place but with people, especially family.

Teaching the Holocaust without Traumatizing your Students

Teaching without Trauma

When teaching the Holocaust, teachers sometimes say, “That was a successful lesson; I had every student in tears.” Students in tears are not students who are learning.

Distraught students do not ask, “Why did this happen?” They ask, “Why do I have to learn this?”

Here are some tips to help your students understand the Holocaust without being traumatized by it.

Teach through Empathy, not Role-Play

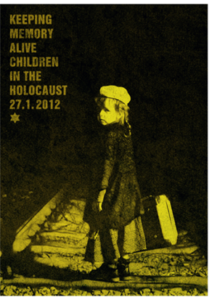

From Keeping the Memory Alive, Yad Vashem 2012. Artist: Petra Nehera.

One common approach to history lessons is to have the students put themselves in the victims’ shoes. “If you had to leave everything behind except one suitcase,” we ask them, “what would you pack?” Although this seems like a good idea, in the case of the Holocaust, it is a recipe for trauma. Trying to imagine losing your home, your parents, or your children does not facilitate learning, or even empathy. It only puts you in a terrifying place you do not want to be.

Do not ask, “How would you feel?” Instead, ask, “How do you think they felt?” The phrasing of this question leads to empathy and avoids trauma.

Equally fundamentally, the exercise in trying to understand how it felt “to be there” is futile. Our students cannot fathom what it means to be hungry. “Starving” to them means it’s been three hours since breakfast and, oh, lunch isn’t for another ten minutes! None of us, thank G-d, can really understand what it was like to be in these situations.

If we give our students the chance to empathize, to consider how the people in those situations felt, then the students will begin to relate. They will relate in ways that are natural to them and, therefore, are not traumatic.

Allow your students to react naturally

Teachers often expect their students to be solemn and quiet when learning about the Holocaust: “This is a solemn subject, and you must be respectful.”

The Holocaust is a solemn subject but it is also a difficult subject. If we want our students to understand, then we must allow them to engage with the material. We must let them react to it. If we expect them to be quiet in these lessons, then we are expecting them to disengage and, therefore, not to learn.

Sometimes, you will find that the students’ reaction is anger. Who among us will tell them that is an improper reaction to this story? For many, this anger will be directed at people, but for others, the anger may be directed at G-d. Some teachers fear to teach this material, fearing to drive students to question G-d. We must let students rage, let them question, and let them work through all these feelings. It is better to allow the students time and space to work through these feelings in class where we can help them than to force them to deal with these feelings on their own.

It is important to note that it can be equally corrosive to expect the students to “be strong.” Tears are an equally appropriate reaction to this story.

Maintaining your students' focus

The Holocaust is heavy material that takes a lot of focus. Know your students’ limits. Here are some hints.

1. Expect these lessons to take multiple classes.

2. In each class, stay within your students’ natural attention span. Use no more than one block of their attention on this material.

3. Do not devote the entire class to the Holocaust. Use one block of attention, and then move on to something else, preferably something lighter.

Helping your students process

It often takes students some time to process the material. They may have questions that come up later, or have spoken to an older sibling or parent, who brought up something else. Here are some hints for helping them with that processing.

1. Allow your students to ask questions even if those questions do not seem to be age-appropriate. Answer them simply and straight-forwardly, and move on. Avoiding answering suggests that some answers are too scary for them, which only makes those questions more interesting.

2. Have the regular classroom teacher teach these lessons. This way, students feel they have a resource to go back to when they have questions at a later time.

3. Make sure you have at least one class after the final lesson of the unit, preferably the following week. Do not teach your final lesson on the final day of classes. Be sure that you have a class after they have completed the unit so they can come back and ask questions.

Other Considerations

Additional Thoughts

Many teachers use visits from survivors and field trips to Holocaust museums to enrich their classrooms. Both come with their own challenges. Here are some things you should think about when using these resources.

In addition, there are certain “classic” texts that many teachers use: Number the Stars, The Diary of Anne Frank, and Night, among others. We recommend that you think carefully about these before using them. Here are our thoughts.

Finally, some thoughts about how to talk about bystanders and antisemitism in the context of the Holocaust.

Survivor Testimony

Nothing is quite as powerful as actually meeting survivors and hearing them tell their stories. Meeting a survivor is the ultimate in hearing “human stories.” Survivors can help make the inconceivable tangible and can transform students into the torchbearers of memory.

Nothing is quite as powerful as actually meeting survivors and hearing them tell their stories. Meeting a survivor is the ultimate in hearing “human stories.” Survivors can help make the inconceivable tangible and can transform students into the torchbearers of memory.

This tool must be used with care, however. Not all survivors’ stories are appropriate for all age groups. For elementary and middle schoolers, if you are interested in inviting a survivor to testify, you should meet with the survivor before extending the invitation. At this meeting, explain how important it is that the students not be traumatized. Primary and middle-school students should not be presented with a survivor whose story includes horrific descriptions of life and death in the camps. A survivor who spent the war in hiding would be a better choice.

By high school, students may be prepared to deal with more difficult stories. You should still understand the survivor’s story beforehand and use good judgment in choosing testimonies that will correspond with your students’ cognitive and emotional needs.

For a more complete discussion of using survivor testimony, and how to prepare for it, please see the discussion of it on Yad Vashem’s website.

Field Trips to Holocaust Museums

Class visits to Holocaust museums, memorials, and educational centers can provide students with special opportunities to gain awareness and knowledge about the Holocaust. As with all field trips, preparation is essential to the success of the trip. Students should only visit these sites after they have had the chance to study and discuss the Holocaust in class, including discussing what they might see at the museum. You should prepare specific activities to do at the museum to better guide your students’ learning process during the field trip itself. And, of course, follow-up discussion is crucial.

Class visits to Holocaust museums, memorials, and educational centers can provide students with special opportunities to gain awareness and knowledge about the Holocaust. As with all field trips, preparation is essential to the success of the trip. Students should only visit these sites after they have had the chance to study and discuss the Holocaust in class, including discussing what they might see at the museum. You should prepare specific activities to do at the museum to better guide your students’ learning process during the field trip itself. And, of course, follow-up discussion is crucial.

It is important to note, however, that such field trips are not appropriate for all age groups. Holocaust museums tend to be aimed at an adult audience and tend not to shy away from the difficult aspects of the story. Students younger than middle school are generally too young for such museums. Middle and high schoolers should be carefully prepared for what they might see.

Using the "Classic" Texts

What about the Holocaust standards: books like Number the Stars, The Diary of Anne Frank, and Night? Should you use them?

We recommend that you do not. Here’s why.

Fiction

Many of the books that are commonly used to teach the Holocaust are works of fiction: books like Number the Stars, The Devil’s Arithmetic, and The Book Thief. Although these are all well written books, we advocate using true stories rather than fiction. The problem with fiction is that it is hard to know which parts of it are based on truth and which are exaggerated or made up for dramatic effect. This makes these stories too easy to dismiss. There are so many well-written true stories available that there is no reason to use fiction.

Many of the books that are commonly used to teach the Holocaust are works of fiction: books like Number the Stars, The Devil’s Arithmetic, and The Book Thief. Although these are all well written books, we advocate using true stories rather than fiction. The problem with fiction is that it is hard to know which parts of it are based on truth and which are exaggerated or made up for dramatic effect. This makes these stories too easy to dismiss. There are so many well-written true stories available that there is no reason to use fiction.

The Diary of Anne Frank

One of the most commonly read true stories about the Holocaust is The Diary of Anne Frank. This story can teach a lot about what life was like for children in hiding. Anne is similar to middle schoolers everywhere, in her hopes, dreams, and fears. However, for the length of the book, this story does not teach as many aspects of the Holocaust as some of the other books about children in hiding available from Yad Vashem. The fact that Anne does not survive also makes this story more traumatic than other stories. Consider other options, such as The Daughter We Had Always Wanted or I Wanted to Fly like a Butterfly, to teach about children in hiding in place of Anne’s diary. If you do choose to use the diary, we recommend discussing how it ends with your students before you start reading.

One of the most commonly read true stories about the Holocaust is The Diary of Anne Frank. This story can teach a lot about what life was like for children in hiding. Anne is similar to middle schoolers everywhere, in her hopes, dreams, and fears. However, for the length of the book, this story does not teach as many aspects of the Holocaust as some of the other books about children in hiding available from Yad Vashem. The fact that Anne does not survive also makes this story more traumatic than other stories. Consider other options, such as The Daughter We Had Always Wanted or I Wanted to Fly like a Butterfly, to teach about children in hiding in place of Anne’s diary. If you do choose to use the diary, we recommend discussing how it ends with your students before you start reading.

The Smithsonian Magazine recently published a fascinating discussion of why Anne Frank’s diary is somewhat problematic. Among other things, they point out that this diary was entirely written before Anne experienced any of the true horror of the Holocaust. “Frank wrote about people being ‘truly good at heart’ three weeks before she met people who weren’t.”

Night and Maus

Other than Anne Frank, the most famous books about the Holocaust are probably Elie Wiesel’s Night and Art Spiegelman’s Maus. These are very well written books that tell true stories. They are also very dark and difficult. In many ways, these books lay bare the PTSD of both the survivors and their children. As such, they can be a fascinating study. As such, however, they are traumatic and require a nuanced understanding of the Holocaust prior to reading. We recommend waiting on these until high school. Whenever you use them, preparation is essential.

Other than Anne Frank, the most famous books about the Holocaust are probably Elie Wiesel’s Night and Art Spiegelman’s Maus. These are very well written books that tell true stories. They are also very dark and difficult. In many ways, these books lay bare the PTSD of both the survivors and their children. As such, they can be a fascinating study. As such, however, they are traumatic and require a nuanced understanding of the Holocaust prior to reading. We recommend waiting on these until high school. Whenever you use them, preparation is essential.

Perpetrators, Bystanders, and Upstanders

It is easy to dismiss the perpetrators of this atrocity as inhuman monsters the likes of which have not been seen since. This perspective fails to recognize that like the victims, the perpetrators were regular people with regular lives. We must recognize that these terrible things were done by people, not by monsters, so that we can learn from them.

The bystanders were regular people with regular lives too. Bystanders fell into three categories: 1) those who joined the perpetrators; 2) those who did nothing; and 3) those who helped the victims (called by Yad Vashem the “Righteous among the Nations”). We must help our students to understand what makes a bystander a perpetrator, why most people did nothing (and why it often made sense to do nothing), and why some people risked everything to help strangers. These are lessons our students can apply to modern life.

When does a bystander become a perpetrator? Some cases are clear. When “bystanders” participate in physical abuse or murder, they become perpetrators. However, there are many ways for a bystander to become a perpetrator beyond actually participating in the violence. When people stand by and cheer as the violence occurs, they are collaborating in that violence. When people go to rallies and cheer as the speaker talks about hate, about isolating communities, or about committing violence, they collaborate in the violence that arises out of that hate speech. During the Holocaust, when people reported their neighbors to the police, knowing that the police would arrest them for being Jewish, they were perpetrators too. We must teach our students to recognize all the ways that “bystanders” participate and collaborate with the perpetrators of violence.

What can or should you do if you witness others subjected to unfair treatment? Witnessing bullying and racial hatred, unfortunately, is a situation in which our students may find themselves. In most cases, we want to encourage them to see how they can help. However, we must also recognize that during the Holocaust, in many cases it made sense to do nothing. Are you required to risk your life to help someone in need? If helping a stranger means risking your family, is it worth the risk? These are difficult questions that we must discuss with our students.

Many people during the Holocaust did choose to help, even at the risk of their lives and their families. Many people were saved because strangers chose this more difficult path. The people who chose to help did not all come from the same walk of life. They did not all have power. They did not all feel protected from the Nazis because of their position. Many were not – many lost their lives. And they did not all help for the same reasons. Some helped because they knew someone. Some helped because they felt sorry for someone who came to their door and chose to hide them rather than send them away. Some helped because they simply felt it was the right thing to do. By understanding the breadth of people who were willing to help, our students can understand how they might find the courage to help someone in such need.

Putting Nazi Antisemitism in Context

A cartoon from Al-Watan, a modern Arabic newspaper, depicting a Jew with a sack of money worshiping at an altar that is also a safe.

The Nazi ideology drew on both long-standing stereotypes and newer visions of genetics. Almost as long as Christianity has been in power in Europe, there have been people who believed that the Jews were evil, in league with the devil, and conspiring to take over the world. Nazi ideology combined this age-old hatred with a newer science. As scientists began to understand genetics in the late 1800s, racists gravitated to the idea that some people had better genes than others and that bad genes could ruin the purity of a race.

The Nazi implementation of antisemitic hatred was more deadly than any that had come before. However, we often incorrectly imply that the Holocaust was a great conflagration of hatred that stands alone and apart from everything else. This hatred has ancient roots in Europe.

This hatred did not disappear with the Nazis. Antisemitism has been around for thousands of years and continues today.

When we end our Holocaust education with 1945, we give our students the idea that the Holocaust was a great antisemitic catharsis, after which the Jews could live in peace. We must remember the Kielce Pogrom of 1946, which drove many survivors back to what had been concentration camps and were now displaced persons camps. We must remember the many Jews who opted not to go home at all, knowing that they would still find violent antisemitism there.

For our students to truly understand the lessons of the Holocaust, we must teach them about the origins and continued problem of bigotry and hatred, and how to fight it in all contexts.